“Why Do They Do That?” with Teepa Snow

Teepa Snow is one of the country’s leading educators on dementia. She joined AFA for a webinar answering a question that caregivers of individuals living with memory loss ask themselves regularly, “Why do they do that?”

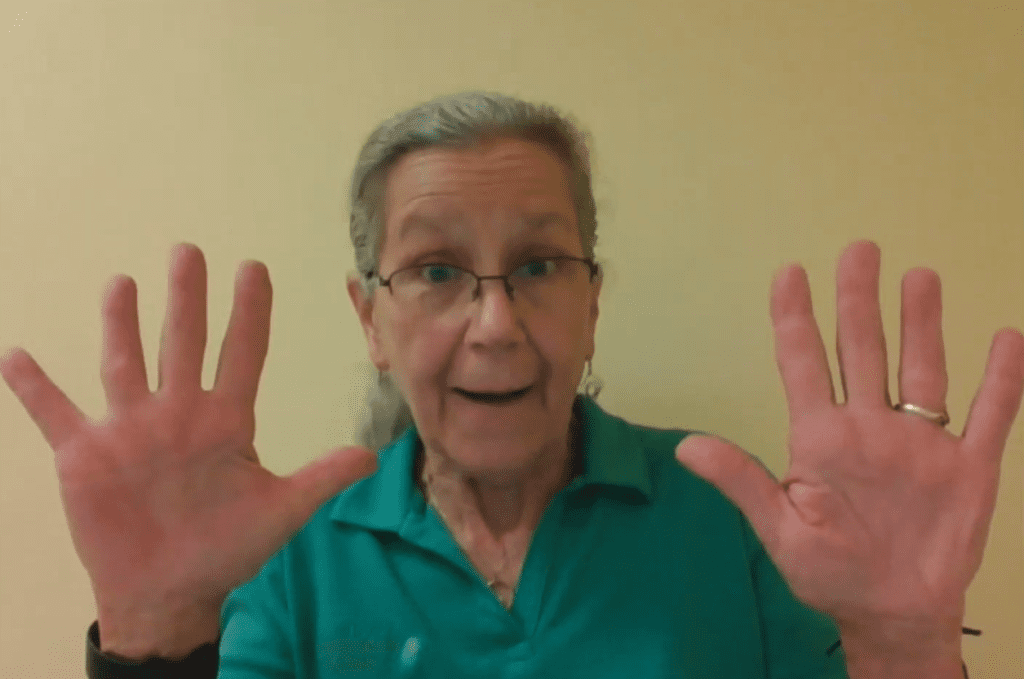

SNOW TAKES A HANDS-ON APPROACH TO EDUCATING – LITERALLY

She shared her understanding of symptoms and situations of dementia in an AFA webinar. In explaining how Alzheimer’s and other dementias affect a person’s abilities, she held up her hands. She explained that the thumb, index finger and middle finger are wired to the part of the brain that allows us to perform a skill, such as button a shirt or unscrew a lid.

The ring finger and pinkie are for tasks that require strength, such as gripping a hammer. “In every form of dementia that we know about, the dementia will rob you of skill before it takes away your strength. Instead of three skillful fingers and two strong, you end up with five strong and no skill.”

Without this awareness, it’s common for caregivers to see their person as the problem and think they’re being uncooperative. “One of the reasons people do what they do is because they’re losing their skills in a variety of areas of function. If they’re losing skill, who needs to develop skill so that things can still be done in a reasonable and accurate way? The answer is, we do.”

In attempting to understand why individuals with memory loss do what they do, Teepa Snow says we need to turn the tables on ourselves. “We need to understand our role and possible ways of making a change to respond to symptoms and situations so we can get a different outcome. We don’t like what is happening, but we’re the ones who can most effectively change because they’re already changing.”

HOW THE BRAIN IS CHANGING

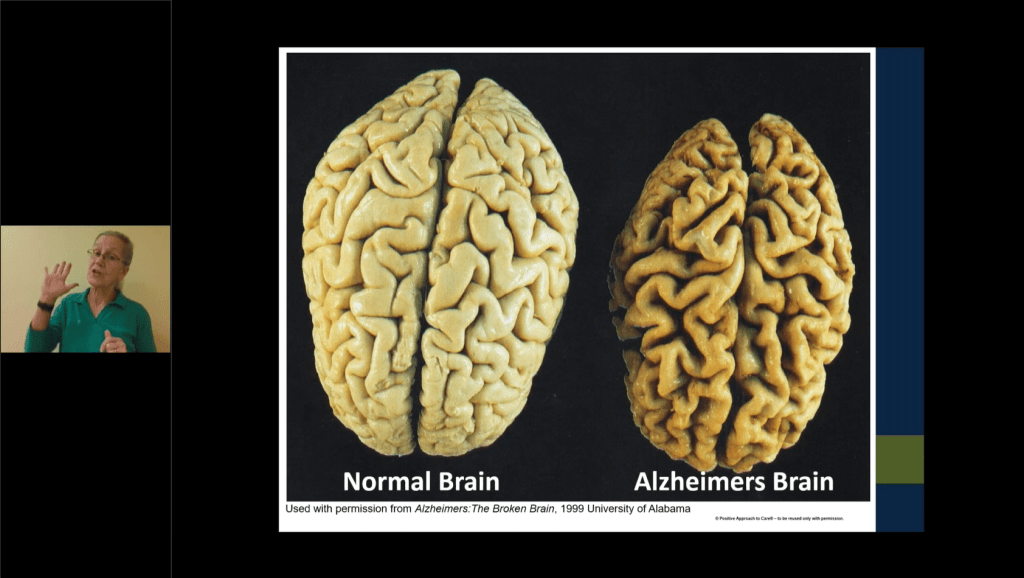

To illustrate why individuals with memory loss do what they do, Snow showed a slide comparing two brains. These brains came from two men, who had died at the same age and physical size. However, one had died in a car accident and the other after living with Alzheimer’s for a decade.

The Alzheimer’s brain looked shrunken and withered in comparison to the healthy brain. “If you can’t see something, you say, ‘Why are they doing this?’ One of the reasons they’re doing this is because their brain is deteriorating. By the end of the disease, you will only have one third of your brain tissue left.”

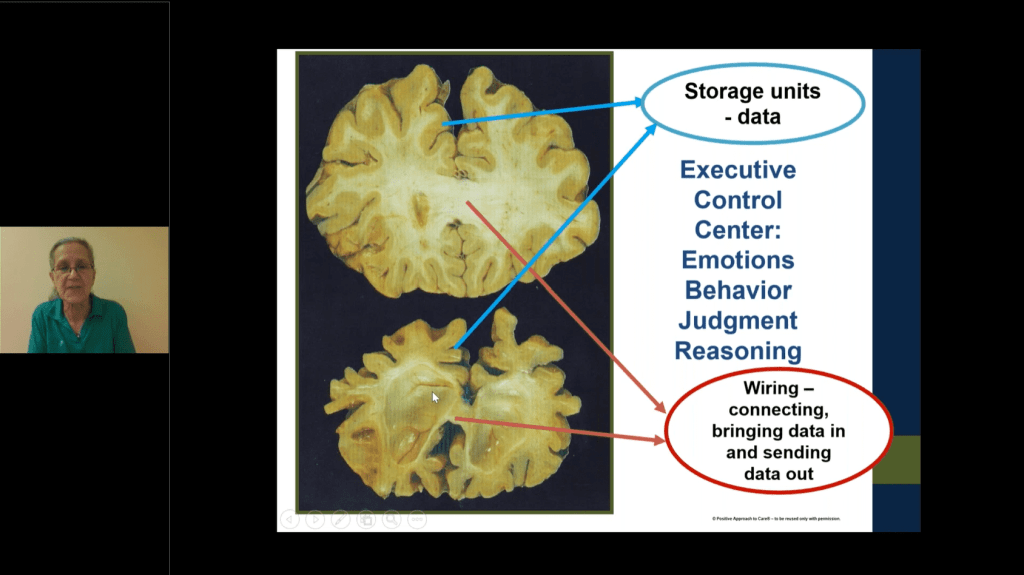

Dementia brains have lost their connectivity, she says. She explained that the top part of the brain contains white matter, “the wiring.” It is the part of the brain that allows you to get data from one part of the brain to another.

“Without that wiring you can’t send messages.” The outside edges of the brain contain “the dark-colored stuff called gray matter. That part is where you store things.” Over the course of the disease, she says, “I’m losing my wiring. There’s still a fair amount of storage capacity. I just can’t get things in and out, and the prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain that can’t do anything on its own.”

Teepa Snow said that in a healthy brain, the hippocampus performs three functions.

1) It helps us learn and remember what we’ve learned.

2) It acts as a way-finder.

3) It helps us understand the passage of time.

She picked up a water bottle to demonstrate. “I learn that water quenches my thirst. The second thing it [the hippocampus] helps me do is find my way to things that help me, that I need. The third piece of this that the hippocampus takes charge of is ‘how long has it been since I’ve had something to drink?’”

But someone in the late stages of dementia may respond differently. Even if they’re thirsty, they might turn the bottle upside down or shake it. They don’t recognize what it’s for. Or, “even more frustrating,” Teepa Snow said, they may manage to unscrew the top and then pour the water on the floor. This may prompt the caregiver to respond in a raised voice. “Here’s the challenge,” Snow said. The person didn’t know he was thirsty. The caregiver assumed he was and handed him a water bottle thinking it would click into place.

“You’re going to want to do something like this,” she said. She smiled and pointed to the water bottle in their hand while making a gesture of putting an imaginary one to her mouth. “You can hold the container until they take the first drink and then understand. You’re substituting for their prefrontal cortex that isn’t able to do the job it used to be able to do.”

WHAT TO DO WHEN THE DISEASE PROGRESSES

In late stages of the disease, people also lose much of their vocabulary. They may also lose the ability to understand what people are saying. Your person may become agitated and start yelling in crowded places because they are unable to separate background noise from conversations. They are overwhelmed. The wiring in the sensory motor area of their brain is fraying. “We want to use our big brain with so much wiring to try to figure it out. We can say, ‘They don’t get it.’ Let’s rethink this because we need to make decisions that are more consistent with what we can figure out.

“Dementia is not an easy journey. It’s not an easy way to live life. But it sure gets a whole lot better when we decide to come together and work together to make a difference in a positive direction.”

Adapted from the AFA webinar “Why Do They Do That? Understanding Symptoms and Situations of Dementia.” This webinar launched AFA’s November Alzheimer’s Awareness Month in 2022.