A growing number of memory choirs provide joy and hope to individuals with dementia and their caregivers.

Creating the Precious Memories Choir was far from the minds of Edith Lawrence-Hilliard and Keretha Cash when they attended an Alzheimer’s conference in Madison, WI, in 2019.

“The conference brought in a choir from Milwaukee, and we were a bit perturbed because we have good choirs here in Madison, and we wondered why they were bringing in one from Milwaukee,” Lawrence-Hilliard says. “When the choir was introduced, it was announced that the majority suffered from dementia and Alzheimer’s and included their caregivers. We looked at each other and said, ‘Ah-ha, Madison doesn’t have a choir like that.’”

So along with Dr. Fabu Carter, senior program manager for retention, event programming and sponsorships at the Wisconsin University-Madison Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, they decided to create one, meeting at CocoVaa Chocolatier to eat chocolates and brainstorm, ultimately choosing to focus on gospel music.

“Spirituals and gospel are African Americans’ great gifts to this country and the world,” says Carter, who is also the senior program manager for recruitment and retention with African Americans Fighting Alzheimer’s in Midlife at the research center.

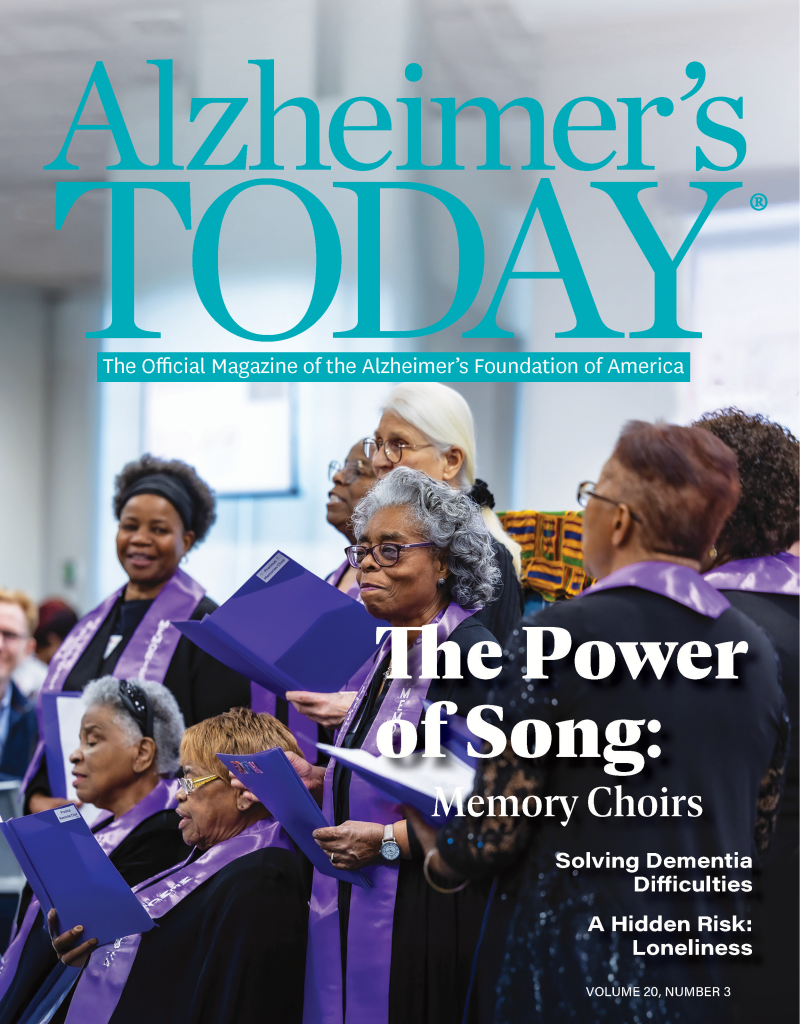

Starting with five African American members, then stopping during the pandemic, they now have 13 members, Black and white, who perform at nursing homes and in malls. Cash and Carter are choir co-chairs; Dr. Sheryl Henderson is director. Singing experience is not required.

“We work with you where you are,” Carter says. “No one will turn you away.”

Choir members and audiences are touched by the messages of the lyrics. One song in particular, “I Need to Survive,” stood out for Cash at a performance.

“I felt the atmosphere and spirit of the place change.

We need people to survive and people with Alzheimer’s need to know their families want them to survive. That’s indicative of our mission.”

Gleeful Choir

Caregivers overwhelmingly describe the Utah-based Gleeful Choir as a source of joy, emotional relief and meaningful connection with both their loved ones and with a wider community of caregiving peers. Choir director Emily Christensen formed Gleeful Choir in 2018. As a music therapist working in memory cafes and hospice care, she had heard about memory loss choirs. She worked for Jewish Family Services, which had a music and memory program, so she collaborated with those involved to form the choir. It meets weekly at the local library for a one-hour rehearsal and 45 minutes of refreshments and socialization.

She’s experienced surprise at her choir members’ ability to sing in rounds, with each side taking its part for songs like “Downtown.” The choir gives five or six concerts a year at Alzheimer’s walks, senior centers and conferences on matters dealing with aging.

“They do an amazing job. I did some research and found that people with dementia are able to learn new material week to week.”

The choir is fun for the memory loss participants and for their caregivers who form friendships that extend past the time when their person has died. Christensen, who has a private music therapy practice, sees music as one of the most powerful ways to connect.

“They can do so much more in a choir than in other areas of life. I’m always amazed at what people can do.”

Giving Voice

In the Twin Cities of Minnesota, Giving Voice formed in 2016. It was such a success that two more memory loss choirs were created, then two more. Eyleen Braaten, executive director since 2021, said the decision was made to help others form their own.

“We realized we could teach people to fish rather than give them the fish. We really see us now as being an organization focused on inspiring and equipping communities to do the work. More singing is better.”

Since 2017, Giving Voice has helped launch more than 70 choirs in the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. This fall, they expect 15 more in rural Minnesota and Wisconsin. They accomplished this by developing a tool kit as a guide, promoting it in senior centers, memory cafes, conferences and with the Rotary Club, “the doers.”

“The act of making music together taps into abilities that remain strong even as dementia progresses, fostering a sense of purpose, belonging and emotional well-being,” Braaten says. “Our choirs not only uplift spirits but also break down the isolation that often accompanies dementia, creating a space where every voice is valued.”

Choirs like these are part of a rapidly growing field known as neuroarts, she said.

“We are calling it a movement. We have choirs that are starting with our tools every semester.”

Giving Voice network choirs across the country and tool kits for forming your own choir can be found at givingvoicechorus.org.

“Alzheimer’s doesn’t wait. We have to get out in the community and make it happen. The magical part of singing is that it’s accessible. Music meets you where you are. Our No. 1 goal is to change the narrative of living with Alzheimer’s.”

And it connects people in surprising ways. Braaten remembers Emily, a daughter who used to bring her mother, who had been nonverbal for years due to her condition, to the weekly rehearsals and her mother sang every song. One day, after singing Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You,” which had been Emily’s wedding song, her mother looked right at her and said, “Emily, I love this song and I love you.” It was the first time her mother had known her and called her by name in years.